The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) thrives on interconnectivity, enabled by industrial networks. In this note, I explore the requirements of industrial networks, tracing their origins and evolution. I examine Fieldbus networks like PROFIBUS and DeviceNet, alongside Ethernet-based industrial networks such as EtherCAT and Ethernet/IP. The role of wireless technology and 5G in industrial automation is also discussed, including key enabling technologies like Dense Heterogeneous Networks and Full Duplex wireless. 5G shows immense potential for IIoT and Industry 4.0. Additionally, I highlight the significance of OLE for Process Control (OPC) as a crucial enabler of IIoT and analyze the security requirements in Operational Technology (OT) environments. Finally, I discuss the opportunities emerging from these advancements and the challenges that must be addressed for widespread adoption.

I. INTRODUCTION

Advancements in technology as well as significant cost reduction of electronics has had a major impact on industrial control systems. For instance, before the inception of electronics, control was performed mechanically however, as technology progressed, mechanical control systems were replaced by electronic control loops which make use of relays and switches to control transducers such as indicator lights and electrical motors [1]. Further advancements in technology has resulted in the use of Integrated circuits and microprocessors which not only make control systems more effective but also enable digital communication with field devices as well as between controllers. This has resulted in the development of several industrial communication protocols and networks. It is these networks that form the backbone of Industry 4.0 or the Industrial Internet of Things. Industrial Internet of Things (IIOT) or Industry 4.0 relies heavily on the interconnectivity of devices and uses advanced technologies and applications such as 5G, Cloud computing and machine learning to enable efficient monitoring and control of industrial processes whilst reducing costs in Capital Expenditures (CAPEX) and Operating Expenses (OPEX) [2].

This note details the developments and applications of communication protocols. The different industrial domains that these networks are used are discussed in Section II as well as the requirement of these networks in these domains. A background of industrial networks is given in Section III. Ethernet Based networks are then discussed in Section IV. 5G technology is discussed in section V and OPC is discussed in section VI. Security is discussed in section VII and finally, opportunities and challenges of these networks are discussed in Section VIII.

II. APPLICATION OF INDUSTRIAL NETWORKS

Industrial networks are used in almost every situation that requires machinery to be monitored and controlled. Examples of such industries include manufacturing, food processing, chemical refinement and electricity generation. Before providing a detailed discussion of industrial networks. It is important to look at the different domains that these networks are used in order understand the requirements of these networks.

A. Industry Application Domains

The industries mentioned above can broadly be classified into discrete manufacturing, process control, building automation, utility distribution, transportation and embedded systems [3].

Discrete manufacturing is when the product being made is in a stable form when it moves from one step of the manufacturing process to another. An example of this is the manufacturing of cars or tools. This process can successfully be broken down into sections that are autonomous and interconnection of these sections is generally done at a high level. This can be contrasted to process control which involves systems that are more dynamic and interconnected. An example of this is steel smelting or petroleum refinery. These industrial processes require that all the plant equipment be available. In this case, the industrial processes are also characterised by having all the equipment interconnected at a low level [1].

Another application is in the building automation space. This field covers several aspects such as access control, security, survalliance and condition motoring. The networks involved here are geared more towards monitoring than control. It is worth noting that the information gathered here is not as critical as in process control and Discrete Manufacturing [1]. Utility Distributions usually cover a large geographical area and therefore tend to resemble discrete manufacturing networks although the equipment that is controlled needs to be connected. The Large physical distance makes interconnectivity of the control network more difficult however it also increases the time it takes for conditions in one section of the process to influence another section [1].

Transport networks are similar to utility distribution networks in that they cover a large physical distance as they deal with fields such as the automation of traffic controllers and the management of train networks. This industry has high safety requirements which has to be taken into account. Lastly, embedded systems involve the control of a single piece of equipment such as the control networks found in cars. As a result, these networks tend to cover very small physical area but have a high demand on safety and are often found in hash environments [3].

B. Requirements of Industrial Networks

Generally, there are three types of information that is transmitted in industrial networks that is Control information, Diagnostic Information and Safety Information [1]. The requirements of industrial networks that enable the communication of this information are briefly highlighted here.

Real time requirements: In industrial control systems, it is required that data is transmitted, processed and responded to with minimal delays as delays in information delivery can significantly affect the effectiveness of control loops [1].

Determinism: Data transfer in an industrial network must be done in a predictable or deterministic fashion. This means that it must be possible to determine when a reply to a transmission will be received [1].

Data Size Requirements: Data Packets transmitted in industrial levels are usually quite small. This is especially true in the low levels of the architecture where only a single measurement may need to be transmitted [1].

Ruggedness Requirements: Industrial networks are often implemented in areas that often experiences harsh environments such as moisture, dust, heat and vibration. Therefore networking equipment must be rugged to prevent damage [4].

Safety Requirements: Because industrial networks are connected to physical equipment, failure of an industrial network can include damage to equipment, the environment or even fatalities [3].

III. BACKGROUND OF INDUSTRIAL NETWORKS

Industrial networks provide the interconnection necessary to enable IIOT. The basis of industrial networking is fieldbus protocols. Initially, fieldbus was seen as a substitute for analog systems such as 4-20mA, however, the technology has expanded and can now be used on many different control layers [1]. The development of Industrial Control networks can be thought of as being divided into three distinct generations which have varying levels of compatibility [1]. The first generation was developed on serial based interfaces. These traditional serial based protocols such as PROFIBUS, CANbus, Modbus and CC-Link with master configurations are still relevant and in use today and therefore will be discussed. The second generation consists of Ethernet-based protocols such as PROFINET, EtherCAT and SERCOS III. These will also be discussed in Section IV. The latest phase that has emerged incorporates wireless communication technologies such as IEEE 802.11.

A. A brief History of Fieldbus

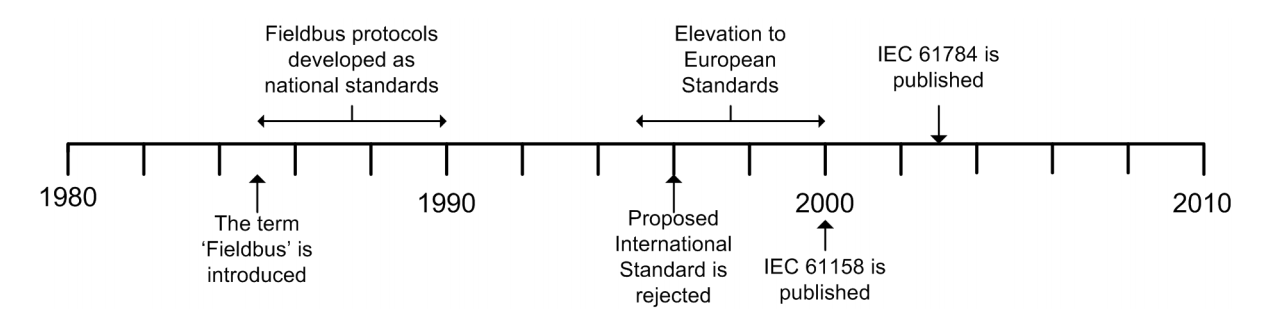

In order to understand the origin and the resulting structure of fieldbus standards, it is necessary to take a brief look at their history [5]. It should be noted that there is a great wealth of literature about the somewhat controversial origins of the different fieldbus protocols, some of which can be found in [3], [5], and [6]. The purpose of this discussion is not to participate in this debate but only to shed some light on the origins of these protocols. It should also be noted that this is not a complete history of all the fieldbus systems. Fig. 1 below shows a simplified timelime for the development of fieldbus.

Fig. 1: Timeline of fieldbus development (From [1])

There were several predecessors to what are known today as fieldbus systems. These emerged as early as the early 1970’s. However, it was only in the mid 1980’s that standardisation of these protocols started. The concept of standardisation establishes specifications in a formal way which comes with a notion of reliability and stability. This in turn secures the trust of customers which inevitably gives a market position [5]. This results in standardised systems having a competitive advantage over their non-standardised competitors. This was the bases of the German-French fieldbus war [5]. The French developed FIP whilst the Germans developed PROFIBUS. Both of these were standardised at a national respective levels and were both submitted to IEC for international standardisation. These two were developed by using very different approaches with PROFIBUS based on a distributed control idea which uses a client server model whilst FIP uses a more centralised control scheme which uses a publisher-subscriber model [5].

These differences resulted in the two systems being used in complementary application areas. A need arose to have the benefits of both systems in a single fieldbus. A group of experts proposed an extension to FIP called WorldFIP which added the funtionality of the client server model. There was also an attempt by the Interoperable System Project (ISP) to enhance PROFIBUS to include the pub-sub communication model. However, this project was abandoned in 1994. The IEC had not made any real progress and had only managed to provide a definition of the physical layer that is found in IEC 61158-2. Meanwhile ISA in America had taken a leading role in developing an international fieldbus standard and contributed the layer structure of the standard that is used today.

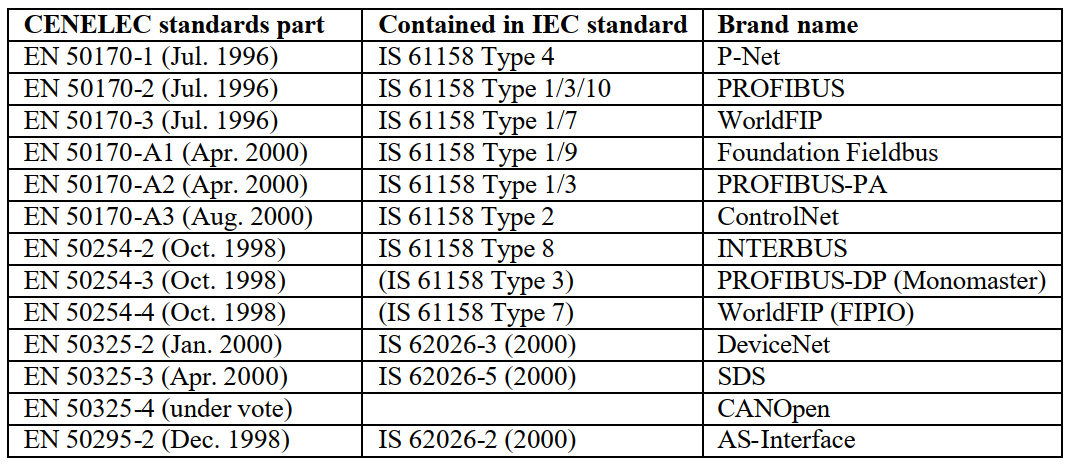

At this point, several fieldbus systems had been installed and were being used in industry. A lot of money had been used to develop these protocols and the IEC had failed to develop an acceptable proposal for a universal Fieldbus. From an economic point of view, it was no longer possible to abandon existing fieldbus protocols in use in order to develop a new unified standard that would be incompatible with existing protocols. Eventually, all the national standards that were under consideration were compiled ’as is’ to the European standards by CENELEC . As a result, every part of the standard is a fully functioning system [5]. Fig. below shows the Contents of the CENELEC fieldbus standards.

Fig. 2: CENELEC fieldbus standards – Dates are for ratification by CENELEC (From [5])

B. Development of Fieldbus

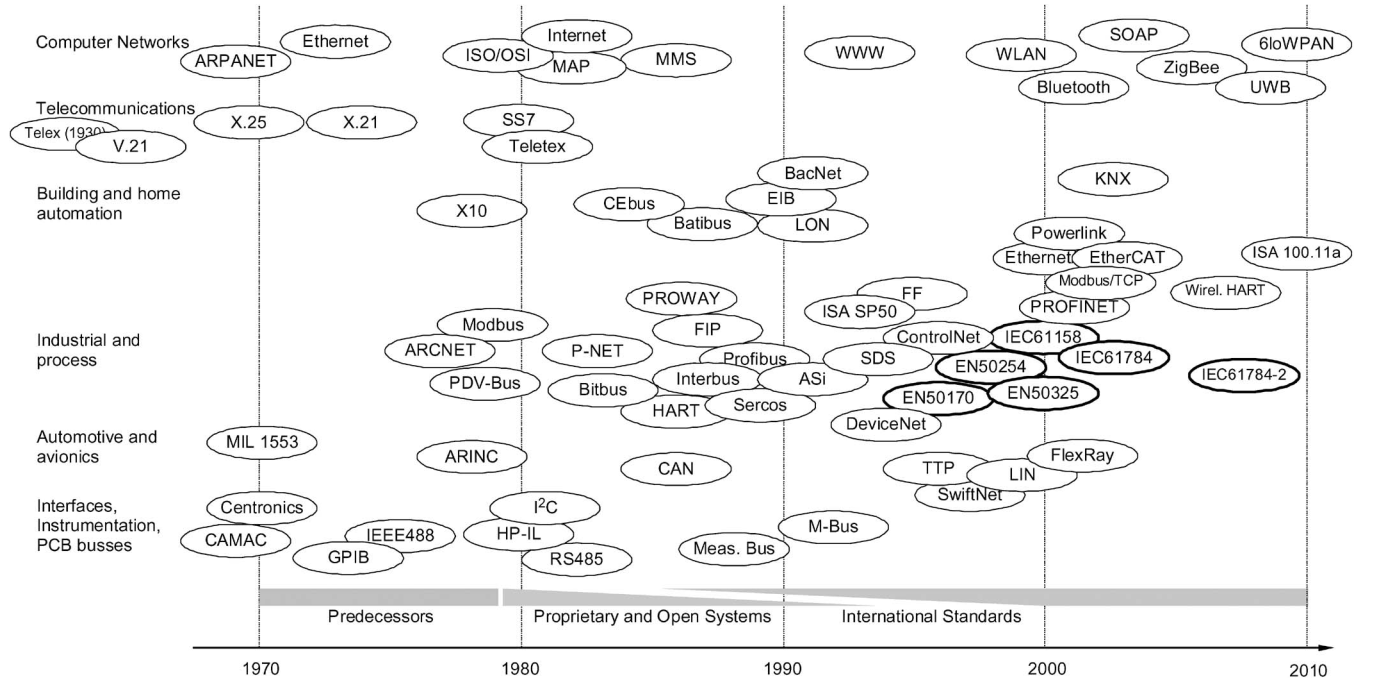

The development of fieldbus aimed to replace the star like point-to-point connections which existed between the controlling computers and the sensor/actuator nodes with a single serial bus. The IEC 61158 standard defines fieldbus as “a digital, serial, multidrop, data bus for communication with industrial control and instrumentation devices such as – but not limited to – transducers, actuators and local controllers” [1]. Fieldbus also brought with it increased flexibility as well as modularity of installations [4]. This development was not only stimulated by end-user requirements but by technological capabilities as well [3]. Fig. 3 below shows a timeline of the development of fieldbus networks in relation to technological advancements in other fields as well.

Fig. 3: Timeline of the development of fieldbus together with development in other fields (From [4])

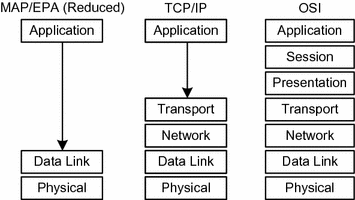

It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the development of fieldbus networks was significantely influenced by development of computer networks. In Particular, the development of the Seven Layer Open System Interconnection (OSI) model shown in Fig. 4 below significantly influenced the development of Industrial Communication Protocols [7].

Fig. 4: OSI Model in relation to Mini MAP and TCP/IP (From [7])

This seven Layer model was the basis upon which many of the complex protocols were developed. The OSI model was first used in the definition of the Manufacturing Automation Protocol (MAP) when the Computer Intergrated Manufacturing (CIM) idea came about. While MAP was both powerful and flexible it did not have much success as it proved to be too complex [1]. As a result, a ”Mini-MAP” or Enhanced Performance Architecture (EPA) standard which was a simplified version of MAP became the basis of several fieldbus definitions [4].

C. Common Fieldbus Protocols

1) PROFIBUS: PROFIBUS is endorsed by SIEMENS and is one of the most well known fieldbus protocols [1]. PROFIBUS uses a token-passing bus access strategy. There are different flavours of PROFIBUS which are tailored for different applications. PROFIBUS-FMS is used for high level cummunicataion which is usually Non-deterministic, PROFIBUS-DP is used to handle low level communication, PROFIBUS-PA was developed to be used in hazadous areas, PROFIdrive was developed for motion control and PROFIsafe for safety applications [4].

2) Controller Area Network (CAN): This protocol was developed in the early 1980s by Bosch to be used in automobiles. It uses Carrier-Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA-CA) on RS232. This protocol only specifies the physical and the Datalink Layers and therefore is not suitable for Industrial automation. However, it is worth mentioning as it is the bases upon which other fieldbus protocols such as CANopen, DeviceNet and ControlNET were built. This protocol ensures short maximum bus access time by specifying eight byte data exchanges. The maximum speed that can be achieved is 500kbits/s. Therefore, CAN and its derivatives are more suited for H1 level [1].

3) ControlNet and DeviceNet: These are expansions of the CAN protocol and are defined in EN 50325 [1]. ControlNet was developed by Allen-Bradely and is now being managed by the Open DeviceNet Vendor Association (ODVA). As the name suggests, it is mainly used for the transmission of control data and prioritises determinism as well as strict scheduling. It uses the Common Industrial Protocol (CIP) application layer. ControlNet is optimised for cyclical data exchange and therefore is suitable for process systems. DeviceNet can be thought of as a variant of ControlNet which is used for device to device communication [3].

4) WorldFIP: As mentioned in III-A This protocol was developed as an enhancement to the FIP protocol in order to meet internation requirements of fieldbus. This protocol only has one variant which is to be used ant both H1 and H2 levels. Data can be transmitted at 31.25kbits/s or 1Mbit/s or 2.5Mbits/s depending on the network requirements [4].

5) Foundation Fieldbus: This protocol is usually thought of as a combination of PROFIBUS and WorldFIP and is now referred to as Foundation fieldbus H1. This protocol was developed by the American Fieldbus Foundation when delays to an international standard where experienced. This protocol specifies IEC 61158-2 physical later and operates at 31.25kbits/s [1].

IV. INDUSTRIAL ETHERNET

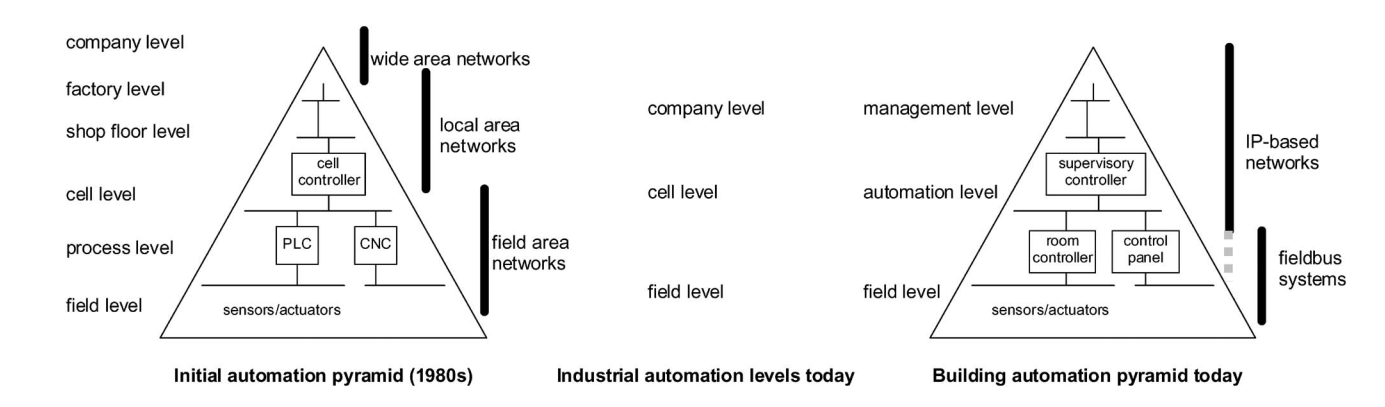

A significant limitation of field level networking methods described above is incompatibility with other layers in the automation pyramid which is illustrated in Fig. 5 below.

Fig. 5: Automation Hirarchy (From [4])

This challenge is one of the main arguments that is used to promote the use of Ethernet in industrial networks [4]. Making use of Ethernet based protocols on the field level allows for the same network technology to be used in both the office world and in industry which allows them to be connected to a single enterprise network [4]. This results in a flattening of the vertical hierarchy within a control network and therefore simplifying the network configuration [1].

While Ethernet as part of the TCP/IP and UDP stack has become the leading standard for both office and home network use, it initially did not gain as much popularity in the industrial space as it is not deterministic and lacks real time capabilities [4], [1]. However, with the advancement of switching and the use full duplex technologies, Ethernet is gaining more popularity in industry [4]. Switching networks relay data received on one port only to the ports which have the relevant receivers. This is contrasted to the previously used hub based networks which relayed data to all ports resulting in a congested physical medium [1]. Full-duplex Ethernet means that transmission and reception can occur simultaneously which eases bus arbitration difficulties [1]. Some Industrial Ethernet Protocols make use of a modified Media Access Control (MAC) layer in order to achieve very low latency and near deterministic responses [8].

A. Common Ethernet Based Systems

1) EtherNet/IP: Ethernet Industrial Protocol was developed by Rockwell and is defined in IEC 61784-1. It is an Ethernet based implementation of the Common Industrial Protocol (CIP) application layer on top of TCP/IP. This means that it uses standard Ethernet physical, data link, network and transport layers while using CIP over TCP/IP. Common Industrial Protocol (CIP) provides a common set of messages that are to be used for automation control systems [1]. EtherNet/IP uses CIP connections over TCP connections in order to establish communication from one application node to another. Standard Ethernet switches are used and therefore there is

no limit to the number of nodes in the system [4]. While EtherNet/IP is compatible with several Internet and Ethernet protocols it has limited real-time and deterministic capabilities. However, the use of full-duplex switched architecture minimizes delays that may have been caused by collisions [1].

2) PROFINET: This is an industrial Ethernet standard that was develoed by PROFIBUS International (PI) [9]. PROFINET which is defined in IEC 61158 and IEC 61784 makes use of PROFIBUS data models on Ethernet. There are three classes of PROFINET i.e PROFINET Class A, Class B and Class C. PROFINET Class A allows a user to access PROFIBUS by making use of a proxy which bridges between Ethernet and PROFIBUS. The cycle time of this class of PROFIBUS is about 100ms and therefore is commonly used for Parameter Data and can sometimes be used for cyclic I/O [10]. PROFINET Class B which is also known as PROFINET Real Time (PROFINET RT) reduces cycle time to about 10ms by making use of a software based real time approach. With these lower cycle times PROFINET RT has found use in both factory and process automation [10]. PROFINET Class C is Isochronous Real Time (PROFINET IRT) and uses special hardware such as FPGAs and ASICs in order to further reduce the cycle time to less than 1ms. Because of this low cycle time PROFINET IRT can be used for motion control [11].

3) EtherCAT: Beckhoff developed EtherCAT with the goal of providing on-the-fly packet processing so as to deliver real-time Ethernet for automation applications. This solution is aimed to be scalable so that it can be used all the way from Large PLCs to Remote IOs to sensor level [12]. This protocol uses standard IEEE 802.3 Ethernet Frames. In EtherCAT, each of the Nodes inserts data into the frame while each frame is passing along the network [11], [12]. This is done in hardware (e.g FPGA or ASIC) in order to minimize latency and therefore achieving the fastest possible response time. It is worth noting that EtherCAT is a MAC layer protocol as a result, it is transparent to higher level Ethernet protocols like TCP/IP and UDP. Up to 65 535 nodes can be connected on a EtherCAT network [11].

4) POWERLINK: Ethernet POWERLINK which was developed by B&R is executed on top of IEEE 802.3. As a result, one can freely select a suitable network topology, cross connection and hot plug. Polling and time slicing are used in order to achieve real-time data exchange. A master node is responsible to control the time synchronisation. Open-source stack software make it easier to implement. Another advantage of POWERLINK is that CANopen is part of the standard which allows for smooth upgrades from previous fieldbus protocols [1].

5) Sercos III: Serial Real-time Communication System (Sercos) combines on-the-fly packet processing (similar to that used in EtherCAT) and standard TCP/IP communication. This is done to achieve real-time Industrial Ethernet with low latency. Sercos III separates input and output data into two separate frames. Sercos III supports ring and line topologies and is as fast as EtherCAT and PROFINET IRT. The network can handle up to 511 Slaves. Sercos III is most commonly used in servo drive controls [4].

REFERENCES

[1] Brendan Galloway and Gerhard P. Hancke. Introduction to industrial control networks. IEEE Communications Surveys Tutorials, 15(2):860–880, 2013.

[2] W.Z. Khan, M.H. Rehman, H.M. Zangoti, M.K. Afzal, N. Armi, and K. Salah. Industrial internet of things: Recent advances, enabling technologies and open challenges. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 81:106522, January 2020.

[3] J.-P. Thomesse. Fieldbus technology in industrial automation. Proceedings of the IEEE, 93(6):1073–1101, 2005.

[4] Thilo Sauter. The three generations of field-level networks—evolution and compatibility issues. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 57(11):3585–3595, 2010.

[5] M. Felser and T. Sauter. The fieldbus war: history or short break between battles? In 4th IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems, pages 73–80, 2002.

[6] James R. Moyne and Dawn M. Tilbury. The emergence of industrial control networks for manufacturing control, diagnostics, and safety data. Proceedings of the IEEE, 95(1):29–47, 2007.

[7] Mohammad Elattar, Verena Wendt, and Jurgen Jasperneite. Communications for cyber- ¨ physical systems. In Industrial Internet of Things, pages 347–372. Springer International Publishing, October 2016.

[8] Bo Xi, Yanjun Fang, Meicheng Chen, and Jingyu Liu. Use of ethernet for industrial control networks. In 2006 1ST IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, pages 1–4, 2006.

[9] Jean-dominique Decotignie. The many faces of industrial ethernet [past and present]. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine, 3(1):8–19, 2009.

[10] P. Ferrari, A. Flammini, and S. Vitturi. Performance analysis of profinet networks. Computer Standards and Interfaces, 28(4):369–385, 2006.

[11] Gunnar Prytz. A performance analysis of ethercat and profinet irt. In 2008 IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation, pages 408– 415, 2008.

[12] Dirk Jansen and Holger Buttner. Real-time ethernet: the ethercat solution. Computing and Control Engineering, 15(1):16–21, 2004.

[13] Leonardo Guevara and Fernando Auat Cheein. The role of 5g technologies: Challenges in smart cities and intelligent transportation systems. Sustainability, 12(16):6469, August 2020.

[14] Ekram Hossain and Monowar Hasan. 5g cellular: key enabling technologies and research challenges. IEEE Instrumentation Measurement Magazine, 18(3):11–21, 2015.

[15] Zhongshan Zhang, Xiaomeng Chai, Keping Long, Athanasios V. Vasilakos, and Lajos Hanzo. Full duplex techniques for 5g networks: self-interference cancellation, protocol design, and relay selection. IEEE Communications Magazine, 53(5):128–137, 2015.

[16] V. Chandra Shekhar Rao, P. Kumarswamy, M. S. B. Phridviraj, S. Venkatramulu, and V. Subba Rao. 5g enabled industrial internet of things (IIoT) architecture for smart manufacturing. In Data Engineering and Communication Technology, pages 193–201. Springer Singapore, 2021.

[17] Li Zheng and H. Nakagawa. Opc (ole for process control) specification and its developments. In Proceedings of the 41st SICE Annual Conference. SICE 2002., volume 2, pages 917–920 vol.2, 2002.

[18] OMRON Electronics. Original commentary what is opc ua? OMRON Industrial Automation, page 1, Jan 2020. https://www.ia.omron.com/product/special/sysmac/nx1/opcua.html.

[19] Wolfgang Mahnke, Stefan-Helmut Leitner, and Matthias Damm. OPC Unified Architecture. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009.

[20] JESSE KU. How to ensure ot cybersecurity. Plant Engineering, 116:1, May 2021. https://www.plantengineering.com/articles/how-to-ensure-ot-cybersecurity/.

[21] Keliang Zhou, Taigang Liu, and Lifeng Zhou. Industry 4.0: Towards future industrial opportunities and challenges. In 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), pages 2147–2152, 2015.

[22] ESSENTRA COMPONENTS. Five major challenges of 5g deployment. Essentra plc, page 1, Dec 2021. https://www.essentracomponents.com/en-us/news/guides/five-majorchallenges-of-5g-deployment.